Kho lưu trữ

Sonni Efron of LA Times on Beky & Ho Thanh Duc

Sonni Efron of LA Times on Beky & Ho Thanh Duc

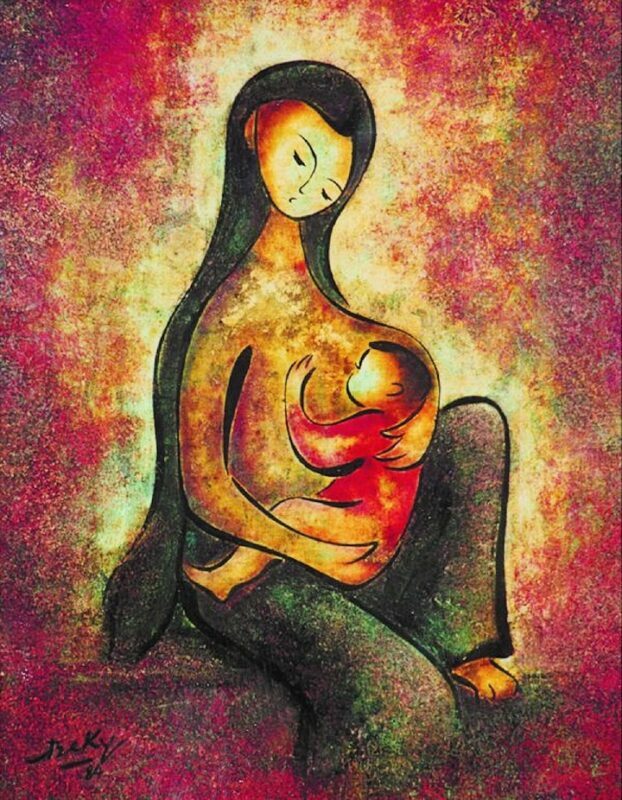

[Black ink slashes white silk, and a lost world emerges.A water buffalo dips one curved horn into a rice paddy. An ancient woman clutches a bowl. A mother comforts her child, touching her cheek to his smaller one in a gesture of infinite tenderness.

These spare brush strokes made Be Ky a celebrity in the Saigon art world at the age of 18. Six months ago, she and her husband Ho Thanh Duc, a renowned collagist, joined a tiny but productive community of Vietnamese artists in exile in Southern California.

And now their focal point is a gallery in Burbank. It is owned by a young etcher, Nguyen Viet, who has been trying to introduce paintings and sculptures by Vietnamese refugees to the American market.

Their works range from traditional brush-and-ink drawings to primitivist sketches, modern acrylics, and post-modernist etching. Some are fierce, such as Ho Thanh Duc’s marbled collages of an anguished Christ. Others are sentimental. Yet the artists express common themes: melancholy, nostalgia, and transcendence.

Westerners should not “think of Vietnam as just a war-torn country,” said Nguyen Thi Hop, 46, who layers watercolor onto silk to produce ethereal scenes of rural life a century ago. “I want to show them that the other side of Vietnam is beautiful and poetic.”

If the art is serene, the artists’ lives have not been.

Be Ky and her husband were both war orphans. At the age of 12, she went to live with an abusive artist who recognized her talent and exploited it.

“He taught me very little, and I learned a lot from other people . . .” Be Ky said through an interpreter at Studio Gallery and Framing Inc. in Burbank, where her recent paintings are hung. “I had to hide my paintings from him.”

By 16, her adoptive father had her hawking her ink caricatures on the streets of Saigon. “If I earned a lot of money, I brought it home and they were very happy. But if the money was little, they would beat me up.”

A French art critic came across her sketches and arranged a one-woman show for the 18-year-old. It sold out. Fame brought more exhibitions in Paris and Tokyo, but relations with her adoptive father deteriorated. One day, she said, she discovered that he had been forging her name on his paintings to bring a higher price for them on the street.

When she confronted him, he struck her across the head, leaving her deaf in one ear. Nearly 30 years later it was that disability that finally persuaded Vietnamese authorities to allow the couple to depart for Manila in 1989.

Ho Tranh Duc’s father died fighting the Japanese, and his mother abandoned the infant to remarry. Duc became a domestic servant.

“They more or less sold me from one family to another,” he said. “One time somebody bought me and used makeup to make me very ugly, and took me out begging.”

An aunt rescued him from the street when he was 11. By his late teens, he was already fascinated by collage. The French artist George Braque inflamed him, but there were also practical concerns. “I didn’t have any money to buy paint,” he said. Instead, he tore the paper from “ ‘Paris Match,’ ‘Life’ magazine, whatever had color in it–even cigarette packs.”

The faces of Christ and Buddha and the drab colors of war figure prominently in Duc’s art. One series of collages that brought him early fame was made of torn fragments of robes given to him by Buddhist monks. One robe was said to have belonged to a monk who immolated himself in protest.

The celebrated couple declined offers to leave South Vietnam before the 1975 communist victory. By 1977, however, they had changed their minds. “We had no freedom to choose our subjects, and we could not produce art under the censorship of the government,” Duc said.

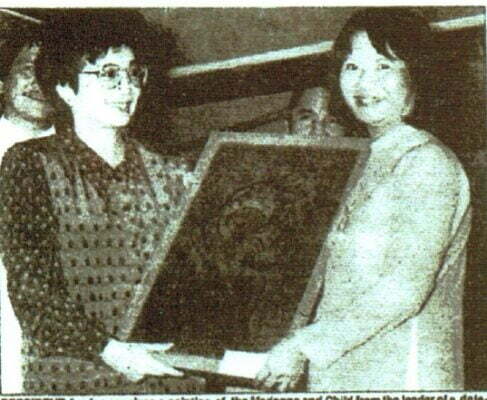

A botched attempt to flee by boat brought Duc a two-year prison sentence. They waited a decade for permission to leave. In 1989, the couple revived their careers with two joint exhibitions in the Philippines, where Be Ky presented President Corazon Aquino with a Madonna sketch.

[President Aquino of the Philippines receives a painting of the Madonna and Child from Beky – the leader of a delegation of refugees during her visit to the Phillippines Refugees Processing Center in Marong, Bataan.]

They have settled in Garden Grove, where they have converted their suburban patio to a studio. At 50, Duc is learning to drive. Be Ky is adjusting to a hearing aid. Her husband jokes that for the first time in their married life he can whisper in her ear–and they can keep secrets from their four children.]